- Home

- Dan Cluchey

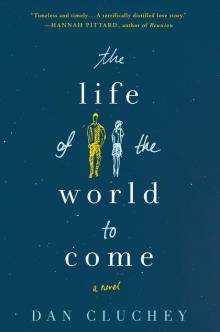

The Life of the World to Come

The Life of the World to Come Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Miriam, who turned my worst facts into fictions

“I am the last president of the United States!”

—JAMES BUCHANAN

ONE

“I HAVE A THEORY ABOUT THE UNIVERSE that, if true, will just blow the lid off of everything,” Fiona whispered to me from her side of the hospital bed.

“Go on.”

“You’re not listening if you’re playing with the chart,” she said, but what she didn’t understand—what she couldn’t understand—was that I could play with the chart and listen at the same time. I relented, although, again, I could have read the chart—actually just a frayed clipboard gripping salmon and citrine forms, and not at all the chart you think of when you think of the many graphs that describe how you are living—I knew that I could have clap-clap-clapped at the chart while listening and done well.

“Okay. So would you agree that time is infinite in both directions? I mean infinite into the past and the future.”

“This sounds pretty heavy, Fiona dear.”

“Do you agree or not?” she inquired roughly, turning suddenly so close that I was sure I could feel the breath of her “not” winnow through the wires of my unripe beard.

“I need to know first where this is going, because it sounds pretty heavy,” I said, chart-free but now snapping at the hair elastic she kept stationed always around her stalky wrist.

“Don’t be a brat. This is groundbreaking new knowledge, alright? This could be Descartes—I’m essentially the new Descartes right now, or Kierkegaard. I mean I could be, if I’m right. Do you agree about time?”

“Do I agree that it’s infinite? I mean, there was a point in the past where no life existed, right?”

“I don’t mean life; I mean time. Even if there’s no life, there’s time and some sort of existence. It’s not nothingness. What I mean is … there’s a venue, even if there are no planets or stars or anything.”

“Got it. Yes, I have no reason to believe that there isn’t an eternal venue that spans out infinitely into the past and the future.”

Fiona’s imagination was a tempest, and this sort of conversation—which I believed that nobody ever had, anywhere—was for us nothing short of typical, and this was simply because half of us was her. With two lazy fingernails, I traced her skin from its point of exposure just above her left elbow and just below the amorphous opening of her pale green gown diagonally down to the wrist for another snap. Again: elbow, wrist, snap.

“Okay,” she continued, “so if time is infinite, then everything that could possibly happen in the universe—say, for example, the formation of Earth—has to happen, not just once, but an infinite number of times.”

“You’re talking infinite Earths?”

“I’m saying the Earth we live on, let’s say it gets destroyed in a billion years. Hundreds of trillions of years go by, and more planets are formed, but they’re all different. If time is infinite, though, then trillions of trillions of years later—or before!—eventually the exact circumstances have to come together again to form another planet exactly like Earth, even if it takes billions of planets similar to Earth but not exactly like it. You dig?”

“I dig,” I said, even though I only maybe half-dug.

“Okay, and, again, time is infinite, so maybe it takes billions of these exact Earth replicas, but eventually one comes along that not only is exactly like Earth, but it develops human life. And maybe every billion or so of those, an exact version of you or me comes along. This would take forever, but that’s okay, because, you know, infinity.”

“This is a conversation that happens after you wake up, Fiona, after we’ve filled you full of the drugs.”

“Come on, just play along for a minute. Just do this. We’ve got this Earth now, okay? At last, we’ve got this Earth that has one of us perfectly re-created—our minds, bodies, souls, even. Everything. One-in-a-kajillion odds—”

“But that’s okay, because kajillions of years and planets have gone by at this point.”

“Exactly! Yes. So eventually, untold eons into the future, there has to be an Earth that has not just you, not just me, but both of us, and at the same time and place.”

“This is very cute,” I whispered into her neck.

“This is serious, though. This is extremely important in case I don’t wake up.”

Here Fiona sighed quietly, and looked away from me for effect. How was it that an actress so gifted could at once be so reliably transparent in her emotional life off-screen? In a moment, somebody was bound to draw back the pigeon-blue curtain separating us from the world. In a moment—but not yet.

“Nobody dies during wisdom tooth removal surgery,” I reminded her gently.

“You don’t know that. You don’t know that.”

“No one dies from this.”

“Fine, but the point is that death isn’t important anyway—not anymore, not after this groundbreaking new theory I’ve developed. Even if I accidentally get quadruple anesthesia and I die, doesn’t matter: we’ll have another life together at some point in the future, actually we’ll have infinite lives, and also in the past. So this isn’t the first time we’ve been together, you know?”

“This isn’t the first time we’ve had this conversation,” I offered.

“Exactly!”

“We’ve had it, I suppose, infinity number of times? And we will have it infinity times again, right?”

“Right.”

“Even if we only have it once every billion lives we spend together, each of which is only one of every billion of our own, solo lives, each of which is only one of every billion Earths, each of which is only one of every billion Earth-like planets?”

I snapped at her hair elastic, too hard this time. Fiona gathered her frantic, splayed curls into a loose rope on the pillow, and looked up.

“Infinity is forever. This isn’t ridiculous.”

* * *

Scientists claim that the universe was created thirteen-point-seven-five billion years ago, a fact that—and I’m sorry, science—but a fact that is absurd to insist we can ever really know. The point is, an extremely long time ago this happened, and things percolated for a bit, and four-point-five-four billion years ago collected remnants of the solar nebula fused together to form the Earth, a massive sphere covered mainly by vast expanses of salt water. It took less than a billion years after that before self-reproducing ribonucleic molecules became life (not sure how), followed thereafter by the invention of photosynthesis, complex cellular organisms, fish, seeds, plants, bugs, and, about two hundred million years ago, mammals. There was an ice age, and there were monstrous, hulking dinosaurs, and then humans emerged a couple of hundred thousand years back. They learned to walk, to catch the fish, sow the seeds, eat the plants you can eat, squash the bugs, and in 2012 I graduated from law school nearly one-hundred-and-fifteen-thousand dollars in debt.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that all stories, if you follow them far enough into the future, end in death, and that nobody who claims to be a true storyteller ought to keep that information from you. Of course, he was almost certainly drunk at the time. He forgot to say where all stories begin if you follow them far enough into the past, but the creation of the universe seems as reasonable a guess as any. I like Hemingway, and I’d like to be true. So it is: like every story, this story begins with the creation of the universe and ends in death. And if it doesn’t, that’s only because this story is not, in truth, over. At the very least, this is how I remember it; a friend recently told me to make my life sincere, and I have sworn to try.

The last time I saw Fiona Fox-Renard I was twenty-six, the universe was thirteen-point-seven-five billion and twenty-six, and Fiona still went by her real last name: Haeberle. She and I had met in college just four years earlier, at the terrible party of a mutual friend of a friend, six weeks before graduation. Said party was one of your standard red-plastic ordeals—strident bass in a dark dorm, the windows overlooking the quad slick with condensation, the children overlooking each other slick with sweat, what air there was in the room nearly tropical despite this being Massachusetts and despite this being April. I had handed in my senior history thesis that morning—States of Confusion: A Political-Psychobiographical Analysis of the James Buchanan Presidency—and my roommates, bless their twisted little hearts, had forced me to attend under threat of being c’mon, dude-d all the way to the grave.

She was the only person at the party who belonged there less than I did—that much I knew right away—but where I sipped drippy in the corner with a lone boot sole pressed tightly to the wall, she bounded briskly to the thumph thumph thumph of a song I believe-it-or-not remember but won’t mention here out of respect for the seriousness of the situation to come. This was not a very good song. I surveyed the room listlessly, monitoring the graceless, exuberant hordes from my perch, and waited for her to stop dancing before I approached. Saying that I waited for her to stop dancing before I approached is a bit like saying that the astronaut waited to return to Earth before taking off his or her space helmet, which is to say I am not a strong dancer. Ten minutes later, loafing behind her in line for the restroom, I calculated what to say, how to look, how to be, when to—

“Hi.”

“Heh—hey. Hey-lo. Hello. How’s … it going?”

Nailed it!

“I’m Fiona. You look like you’re having absolutely no fun.”

“That’s … you’re dead on. I’m emphatically not having fun, although I’m committed to turning things around. Keeping a positive attitude, all that.”

She was lean and confident-seeming, with the breezy look and feel and wit of a flapper poetess. She had the slightest accent I could not place—her voice, upland and high, sounded as though it must have rolled through the wheat fields of America for thousands of years, kicking up the soil, filling up on music and Wisconsin grit. An iconic mole, which on my own face would have succeeded nowhere, rested effortlessly just below the western curve of her lower lip like a goddamn jewel.

“Hmm,” she purred my way. “Have you tried enjoying it from another angle?”

“I’m sorry?”

“I mean, this party is rubbish, right? It’s objectively a bad time. But appreciate it. From another angle. You’re a senior, yes? So appreciate it for its novelty—pretty soon, we won’t have this level of absurdity in our lives anymore. So you can enjoy this … this disaster … as, you know, a piece of pre-nostalgia. Something you can hold on to, later, when your life has turned stale.”

“I like that—I like ‘pre-nostalgia.’ That’s a solid angle.”

Her hair was some new color I wasn’t familiar with from twenty-two years on Earth. She spoke with impeccable diction, and stood with perfect posture, and I was pulled quite quickly into her orbit.

“Look,” she said, “I know this whole scene is a little much, yeah? I get it. You’re too cool for this? Or not cool enough? One of those options, maybe? But those people—that’s your generation out there, rubbing up on each other.”

“My generation.”

“It’s true!”

“My generation is really getting after it.”

“They’re excitable,” she said, mock-thoughtfully pursing her entire face and commencing to absently crack each of her wispy fingers in turn.

“Every time I come to one of these, I like to pretend I’m an anthropologist,” I offered after a torturous beat threatened to end it all before it began.

“Aw. That’s super weird, my new friend. A super weird thing to say to someone you’ve just met. Are you … are you like, some sort of a kind snob?”

Some sort of a kind snob. That’s probably exactly what I am. Exactly. Fiona had recently finished her thesis too—Thirteen Ways of Looking at ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird:’ Modernist Poetry, Modernist Movement—and the fact that she was a double major in theater and dance led me inexplicably to bring up the not-dark but also not-flattering secret of my ineptitude in the latter discipline.

“You cannot be that bad,” she challenged, but she was wrong: I certainly could.

“I am indeed that bad. I am the worst.”

“Ugh! Okay, that’s it; we need to go dance right now.”

Fuck no.

“No, thank you.”

“No, you have to come dance. It is decided.”

Don’t do this to yourself. Don’t do this to yourself.

“I need to be really clear with you on this, okay?” I pleaded faux-desperately, but also actually desperately. “I need you to consider the consequences of your actions: if you make me dance, you won’t ever want to talk to me again.”

“No?” she mouthed mockingly, wide-eyed, already pulling my sleeve toward its inescapable destiny of bewildered flailing.

“Not just that. You’ll never dance again.”

“I love to dance,” she said.

“Not anymore. Not after you go through what you’re about to go through if you make me dance. You can’t un-see what you’re about see. It’ll destroy the whole medium for you.”

By then I had realized that I never had a chance, that she had checkmated me—when? Not when I brought up my failures as a dancer. Not when she brought up her successes as the same. No, it was much earlier. When she put on that devastating sundress? The day her parents met? Thirteen-point-seven-five billion years ago, when nothing at all erupted knowingly into everything there would be? I thought of what Joni Mitchell said about us being stardust, golden, billion-year-old carbon; calibrating even for the fact that I was now quite drunk, I decided then that it must be true, at least in Fiona’s case. She was made up of prehistoric stars—that elegant electric dust—more obviously than anyone I’d ever met.

“Jesus. You weren’t kidding,” said the stardust.

I looked like a monumental idiot, and the music tore through the sopping room like a frightened bird, and all night long she called me “Neil,” which is not my name. Just briefly then, in the humiliating haze, it occurred to me that I’d never cared enough to dance for someone up until this instant, not ever, and certainly not so suddenly. I am not a sudden person.

By chance, we met again the next day: Bettany Skiles, my natty and occasionally brilliant dorm-mate, was screening her thesis film—The Nervous System: A Very Deep Film by Bettany Skiles—in which aspiring actress Fiona portrayed someone’s unlovable daughter, a gaunt and ghostly teenager stricken terminally by ennui.

“Leo,” I corrected her warmly when we nearly bumped into each other in the clinical-white foyer of the campus theater.

“If I sit with you, do you promise not to talk about the film or about me?”

This would prove to be the first of maybe ten thousand instances in which Fiona spoke to me as though we had been smack in the middle of some longer conversation, and I sensed this, I guess, and smiled.

“Of course you can sit with me. You

’re in the movie?”

“You’re the only person I know here who maybe won’t talk about the film or about me,” she explained as her eyes darted frenetically between the smattering of assembled students, looking for recognizable faces from which she could shrink.

“We don’t have to talk about anything,” I answered with my still eyes on hers: twin hazel atoms, agitated, whizzing suspiciously around the room.

“Because we don’t know each other, I mean.”

“I’m sorry?” I inquired, suddenly and strangely and intriguingly hurt.

“We don’t really know each other, so we can talk about anything else. We can talk about the Giants, for example, because I don’t know how you feel about them yet.”

“Right, I—”

“And you don’t know how I feel about them either.”

“Right, so I don’t really—”

“I hate them. I hate the Giants.”

“Alright. Do you mean the New York Giants, or—”

“So we shouldn’t talk about that, probably, but what I’m saying is that we can basically talk about anything, just please not the film and not me. Not me in the film, I mean. Not acting.”

“Fiona, we don’t have to talk about anything. It would actually be … rude, to talk, you know? We’re at a movie, and everyone will be—”

“We’re at a film, Leo,” she breathed, almost inaudibly, and in that moment I saw for the first time in my life a whole beautiful future.

I am not a sudden person, but something in her chased that all away. Stardust, maybe, though looking back it’s difficult to say what parts of that were real. Even then, Fiona seemed infinitely more alive, and yet less lifelike, than the rest; she was ruled by other impulses, governed by other laws passed down from brighter bodies. And right then and there, in the gaping mouth of the campus theater, she snapped me from my present.

Within a week, it was decided that if we were going to be the perfect little love of the century we were going to have to do everything in double-time. And so it was: days of lunch and dinner, days of breakfast and lunch, afternoons spent hastily Venn diagramming our respective circles of friends, nights spent studying each other for the big quiz that seemed certain to come at the close of the academic year. If our nearest and dearest were shocked by the velocity of it all, Fiona and I neither noticed nor cared. Fast love was a business, and at graduation we took dozens of photographs together, correctly suspecting that our later selves would think us smart anticipators.

The Life of the World to Come

The Life of the World to Come